This post was written by Tahani Iqbal, an independent consultant working on tech and connectivity policy in Asia-Pacific.

High-quality internet connectivity is the basis for modern-day economic development, empowering users, driving innovation, and transforming lives.

It is for these reasons that the United Nations (UN) Broadband Commission’s Target 3 is to make sure the broadband-internet user penetration reaches 75% of the world’s population by 2025, and the UN’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation calls for universal and meaningful connectivity by 2030 to support the Sustainable Development Goals.

There is no doubt about the benefits linked to bringing people online. However, it is important to note that internet connectivity is not restricted to building a conducive environment for last mile and rural access providers and services alone. In fact, addressing policy and regulatory bottlenecks throughout the internet value chain — everything from international connectivity, local backhaul, and access networks — to ensure optimal connectivity is critical.

Submarine cable connectivity underpins the global internet…

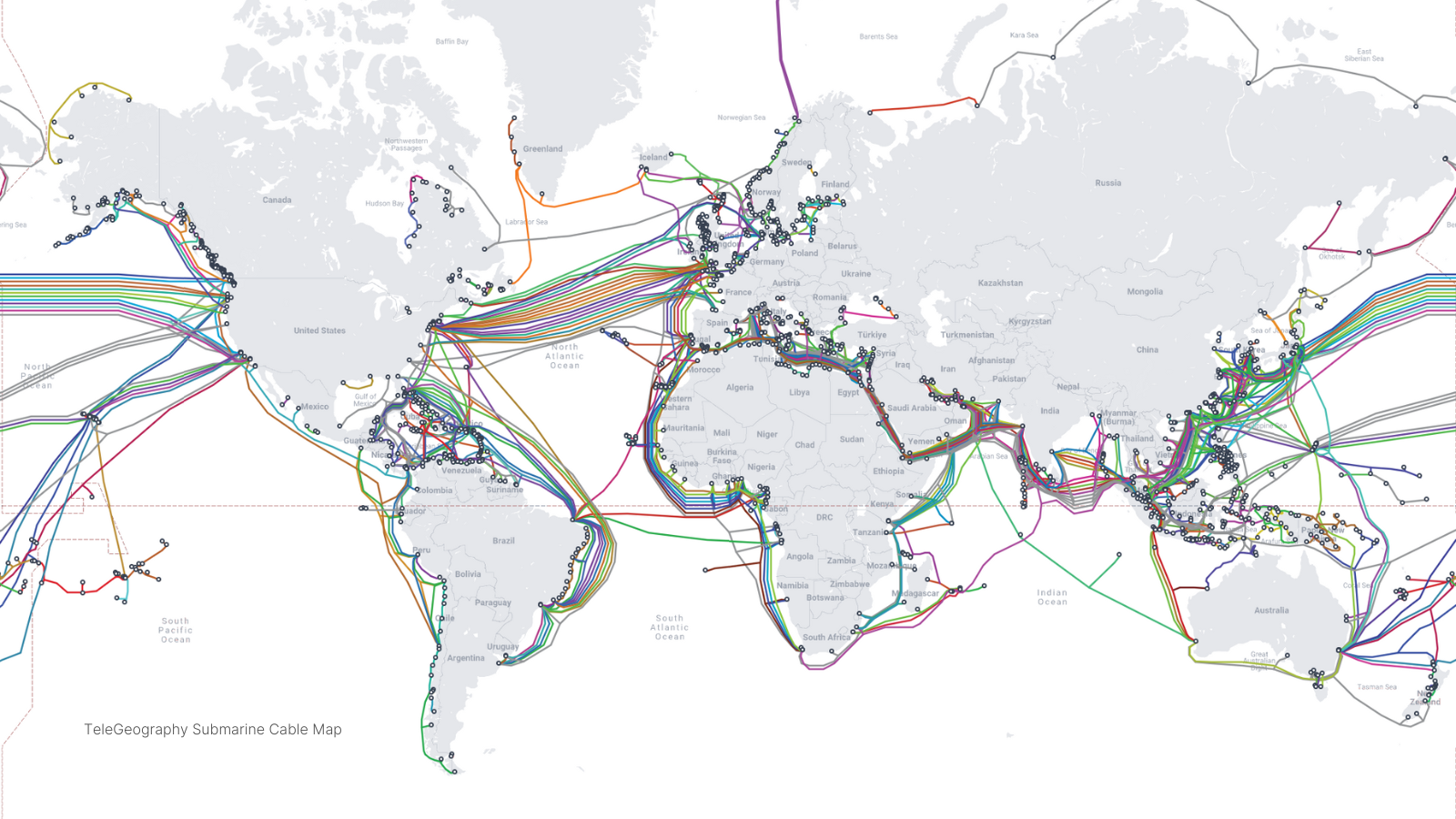

In an interconnected digital world, international submarine cable connectivity is indispensable. Over 90% of all of the world’s internet traffic is carried by these cables.

Submarine cable connectivity enables efficient, reliable, and real-time communication across the world. Recent technological developments coupled with the growing need for greater international transit have spurred the growth of this kind of connectivity, which has implications for affordability and access to digital services everywhere.

Despite this, many policymakers, especially those in emerging markets in Asia and Africa, fail to understand the importance of submarine cable connectivity as a key enabler for digital development. Creating an enabling ecosystem to support these long-term, large-scale efforts will ensure robust and resilient internet networks that can continue to support everyone coming online.

…and demand continues to grow for submarine cable connectivity in the Global South

There are currently 1.4 million kilometers of submarine cables in service around the world, with many more in the works. Submarine cable investments have increased significantly in recent years, and the market is expected to grow from US$235.85 million in 2021 to US$546.78 million by 2028.

According to Telegeography’s 2023 The State of the Network report, international bandwidth has been doubling every two years, with the number tripling since 2018 to 997 Tbps in 2022. The report also states that “Africa experienced the most rapid growth of international internet bandwidth, growing at a compound annual rate of 44% between 2018 and 2022. Asia came in second, rising at a 35% compound annual rate during the same period.”

The burgeoning demand for international bandwidth is telling when not even half of the Sub-Saharan African and South Asian regions are connected to the internet. As of 2022, only 36% and 43% of users in these regions have access to broadband, respectively. There is so much more to be done to facilitate these investments to enable further connectivity and realise the UN’s digital inclusion targets.

Enabling submarine cable investments

What, then, can policymakers do to foster investments in submarine cable connectivity?

Ensuring that the investor environment remains open and competitive, as outlined in the Good Practices for Subsea Cables Policy is certainly a good start.

Subsea cables: what is at stake? A thriving digital economy and achieving universal, meaningful connectivity

Achieving global connectivity requires maintaining and growing the vast network of subsea cables that connect most around the world to the internet.

Given the high-stakes nature of these investments, any local and foreign investor will also look for predictability and transparency when considering a location as a viable landing point for any cable system. In this regard, policymakers should:

Encourage multiple cables landing in diverse landing points within their jurisdiction to provide network resilience and stability and promote competition to achieve affordable connectivity. Singapore has 26 submarine cables across three landing sites located on its Northeastern, Southeastern and Southwestern coasts, while Bangladesh and Pakistan, with far larger coastlines, populations, and bandwidth demands, have just two landing stations each, connecting to two and seven cables, respectively (Telegeography Submarine Cable Map). In fact, the Singapore government is expecting to double the number of cable landings in the country by 2030.

Ensure regulatory certainty, predictability, and efficiency through a nationally coordinated policy for submarine cables. Many local and national agencies are typically involved in permitting and licensing approvals for submarine cable systems, including telecoms, infrastructure, fisheries, environment and conservation, and naval and defence authorities, among others. A coordinated approach with a single focal entity to drive progress in setting up, approving, maintaining, and repairing cables should be implemented. As a best practice, Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) coordinates across multiple agencies for submarine cable approvals, which takes around three months to process. On the contrary, on average, the United States’ Team Telecom security review takes around seven months or longer.

Promote regulations that expedite cable repairs. Cable cuts are common (over 100 each year around the world), and cables need to be repaired frequently and quickly. Restrictive cabotage laws, which typically allow work to be carried out only by locally registered/owned ships, make it hard for specialised internationally-flagged vessels to enter domestic waters to conduct these repairs. Exemptions from these laws to allow foreign-flagged vessels with foreign crews are key to supporting the installation, maintenance, and repairs of international submarine cable systems in a timely manner. The International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC) outlines best practices for protecting and promoting the resilience of submarine cables to maintain the continuity of communications in the event of cable damage. Malaysia and Indonesia’s laws mean that only a single locally registered ship is able to conduct repairs in their waters, and these vessels often do not meet international safety and technical standards, making it hard for foreign investors to consider landing cables in these locations. As a matter of fact, Malaysia’s strict cabotage laws resulted in the country being bypassed as a landing point for the Apricot cable.

Case study: India

In June 2023, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) issued recommendations on ‘Licensing Framework and Regulatory Mechanism for Submarine Cable Landing in India’. A closer look at these recommendations shows many good proposals in the document.

Recommendations such as identifying submarine cables within the Indian territory as critical and essential services, simplifying the process for licensing and approvals across government agencies, identifying protection zones or corridors, making provisions for an Indian-flagged vessel to address repairs in a timely manner, and providing visa exemptions for foreign crew members on foreign-flagged ships, are a good way to incentivise and encourage further investments in this space.

However, the recommendations also propose guidelines for domestic submarine cable systems connecting two cities within India. The costs and environmental implications are likely to be far higher than connecting domestic locations terrestrially. India already has a highly competitive market for submarine cables, with 15 cables in 14 landing stations in five cities across the country. Considering there are only so many viable landing points, it would be important to dedicate these resources to new and planned international cables to meet future bandwidth needs instead.

Furthermore, imposing mandatory ownership requirements on cable landing stations under existing International Long Distance (ILD) and Internet Service Provider (ISP) licences may pose barriers to entry for new licensees. In addition, the average costs of rolling out international cable systems are typically shared across a number of consortium members. If Indian licensees are unable to fund these projects to claim ownership of the Indian segment, this could end up in a situation where new international cable systems bypass the country altogether.

It would be critical for the Indian government to reconsider some of these recommendations when it issues directives on submarine cable system licensing.

The Good Practices for Subsea Cables Policy provides an overview of the best policy and regulatory approaches taken in this regard and would be a useful resource for regulators considering revisions or updates to their subsea cable policies.

About GDIP

The Global Digital Inclusion Partnership is a coalition of public, private, and civil society organizations working to bring internet connectivity to the global majority and ensure everyone is meaningfully connected by 2030. GDIP advances digital opportunities to empower and support people’s lives and agency, leading to inclusive digital societies.